“Security Software Aims to Prevent MT Data Leakage”

Posted by Donald A. DePalma on March 5, 2014 in the following blogs: Technology, Translation and Localization, Best Practices

Even if government agencies and hackers stopped looking at your web queries, e-mail, and phone messages, you would still have to worry about your data security. Why? Both your employees and your suppliers are unconsciously conspiring to broadcast your confidential information, trade secrets, and intellectual property (IP) to the world. How? Through unencrypted requests to Google Translate and Microsoft Bing Translator, routine use of Wi-Fi at coffee shops and airports, and whenever they send translation jobs off to their contractors.

How concerned should you be about this outflow of corporate data? Common Sense Advisory’s 2013 research on machine translation (MT) found that 64% of the 239 respondents say that their business colleagues frequently use free MT services on the web. Sixty-two percent of our total sample expressed concern about it. And because as many as 83% of Americans drink coffee, there’s a good chance that many of them send off confidential documents for translation while sipping a half-skim latte and munching on a cinnamon scone.

Short of disconnecting your company from the web or establishing and enforcing MT usage restrictions across an entire enterprise and at all your suppliers, what can you do? Some machine translation developers have briefed Common Sense Advisory about plans to create a secure in-house or cloud-based MT solution. However, that only solves the employee side of the problem inside the firewall, and requires an alternative MT engine to field their requests. For language service providers (LSPs) translating your content, you can only pray that they adhere to the terms and conditions of the non-disclosures and service agreements that they signed – and hope that you included strong clauses regarding data security and privacy. A solution offered by MultiCorpora and other TMS providers locks down the content for the translation buyer and compels LSPs to translate in a secure, hosted environment, thus blocking access to free online MT.

Lingosec, an Amsterdam-based start-up, has taken a different approach to the problem for both enterprises and suppliers. Managing director Pawel Walentynowicz told us that while his company’s software doesn’t plug all the potential IP leaks, it does stop up a few very big ones. The first is on the enterprise side where Lingosec software installed at the enterprise’s firewall intercepts all outgoing requests to online MT software:

- By default, Lingosec replaces all names, proper nouns, locations, positions, and numbers in the request with tokens that carry no identifying information. For example, it would transform the phrase “according to research about the European market from Common Sense Advisory in Cambridge, United States, 49% of respondents said that…” by replacing identifying information with security tokens. Thus, what’s sent out to the MT engine is a phrase with security tokens replacing the names of cities, countries, and companies: “according to research about the sectokencontinentadj market from sectokencompany in sectokencity, sectokencountry, 21% of respondents…”

- Each of the security token variables corresponds to a hashed number in Lingosec’s software registry. Google or Bing Translator – or any coffee shop eavesdroppers – see just the text with the tokens, which are converted back to the real values only when the translation comes back to your side of the firewall. For numbers, Lingosec generates a random cipher with the same amount of digits.

- Beyond those defaults, the software also allows companies to specify their own tokenization rules to protect things such as chemical formulas, financial and legal terms, other specialized terminology, proprietary processes, and litigation phases. In short, either by default or by custom definition, Walentynowicz says that the software can tokenize anything that could identify a person, company, process, or some other critical piece of information.

LSPs that install Lingosec at their firewall will see the same results for anything that their staff sends off to a free MT engine. However, they can extend this protection out to their vendor supply chain. The software also generates similarly hashed and anonymized files that LSPs can send to their freelancers and translation agency partners. As with the MT requests, the outside linguists see only the tokenized text, thereby protecting the trade secrets of their clients. As with MT submissions, when the files come back, Lingosec uses its hash table to reconstitute the text with the redacted words.

Walentynowicz said that both enterprises and LSPs can integrate Lingosec with Outlook or other e-mail software. Depending on the configuration they choose, they can have the software automatically anonymize or substitute pseudonyms in sensitive parts of the e-mail or attachments, so they cannot be identified by the receiver, but still convey the context of the message.

There are holes, of course. Employees sitting in a Costa Coffee, Terminal 5 at Heathrow, or Wi-Fi-equipped brewpub aren’t working behind your firewall, so anything they send will be open to eavesdroppers and interpretation by the free MT providers who claim rights to using that information for their own purposes. Translations that they request from home won’t be tokenized either, unless their local cable provider installs Lingosec software. However, employees working outside the firewall can login to the company’s Lingosec account via a secure https connection and use the system’s internal interface to prevent leakage when they do request free MT. And LSPs that switch to communicating in e-mail after the initial translation simply bypass those protections.

These problems notwithstanding, if this software works as well as the demo did, then it plugs several major gaps in an organization’s data security framework. Looking at future European Union regulations drafted in response to NSA PRISM, by 2016 companies could be on the hook for 5% of their annual global revenue, if security breaches come to the attention of E.U. data authorities. One way to test it would be for Lingosec to offer the same kind of challenge that LifeLock’s CEO famously did by publishing his social security number, although that experiment didn’t turn out well.

The bottom line: Data leakage via MT and supply chain flaws is a real and present danger to enterprises and their translation suppliers. Software to plug these gaps is just now entering the market.

Full article to DOWNLOAD

Direct LINK to the article http://www.commonsenseadvisory.com/Default.aspx?Contenttype=ArticleDetAD&tabID=63&Aid=20268&moduleId=390

“Internet Threats No One Ever Warned You Against” – Content Security Study by Paul Walentynowicz

One of the biggest internet lies is: “I have read and agreed to the terms and conditions”. How many times have you ticked the box without even bothering to read the text?

Whenever you sign any official document, you read all the clauses carefully, because you know that if you don’t, it may have dire consequences. Yet when using free online tools and applications we are no longer this cautious. When using some services, you automatically agree to their terms and conditions, and when they decide to change them you agree with the new terms and conditions by unawareness without even noticing.

Were you aware of that?

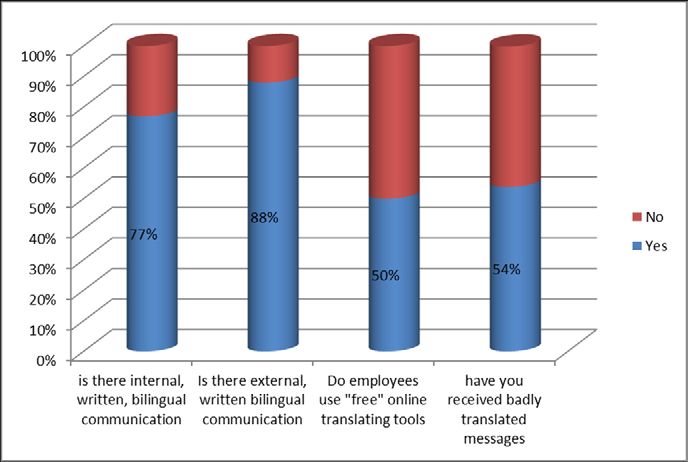

More and more big companies are. Let’s take the Volkswagen Group as an example. Jörg Porsiel from Volkswagen Group’s Translation Management department points out that “for reasons of data security, the use of machine translation on the internet is not permitted throughout the [Volkswagen] Group. Access to the relevant web sites has been blocked.” On the other hand, a contradictory example can be found from a survey conducted by the our company research team this year: about 50 % of the companies interrogated say that they use tools accessible on the internet to translate their multilingual internal and external documents, even the ones classified as confidential.

A section of the results of the our survey

Before examining the consequences, let us take a closer look at the main free online translation services available today. Would you like to know more, read our Content Security Study.

“Don’t throw confidential information out on the street”

Het Financieele Dagblad(“The Financial Journal”)

Those who use free translation tools are giving their consent to make company information available to the public

Information is an extremely valuable possession for most companies. Confidentiality agreements with partners and companies are intended to protect this precious commodity from the competition and hackers. But who gives much thought to the dangers that lurk within the company itself?

A free online translation tool almost sounds too good to be true. It is in fact a fantastic piece of technology that makes it possible to translate words, sentences, and even entire databases. The most commonly used tools are Yahoo Babel Fish, Microsoft’s Bing Translator and Google Translate, which boasts the possibility to translate 69 languages. Almost everyone knows that the quality of these translations is poor, but it does give them an instant idea about the content of a text, perfect for quickly grasping the overall gist of a document. Most users give little thought to how the ‘translation machine’ actually works; they’re just happy if it works.

But suppose, for example, that an account manager with clients around the globe receives a Japanese document and must understand the contents of the document for a conference call the very next morning. The internal translation department or an external translation agency needs more time for the translation than the account manager has. So, as he often does in this type of situation, he turns to Google Translate and, within seconds, believes he has solved his translation problem.

But what happens when you click on ‘translate’? Before so much as a word is translated, the user must agree to Google’s terms and conditions. Section 11 is particularly interesting. ‘By submitting, posting or displaying the content, you give Google a perpetual, irrevocable, worldwide, royalty-free and non-exclusive license to reproduce, adapt, modify, translate, publish, publicly perform, publicly display and distribute any content…” In other words, the account manager has not only violated the confidentiality agreement with the client, but may have also put more or less confidential information from his company out on the street for everyone to enjoy. How many employees naively use online translation tools on a regular basis and how much information is leaked out daily as a result? How often are international confidentiality agreements violated in this manner, simply because employees are not aware of the risks they are taking by using ‘free’ tools?

We don’t know what companies like Google or Microsoft do – or will do – with the information gathered, but we do know that Google is gradually building an information empire. It does this using YouTube (music and video preferences), Google search engine (individual preferences), Gmail and Google + (personal information on users), Google Maps (the entire world on film), Google Docs (information on large quantities of literature) and Google Translate, which collects enormous amounts of sensitive company information daily. We can only hope that, after WikiLeaks, the next leak isn’t a GoogleLeak, as that would mean an unfathomable amount of traceable company information available online.

Companies would therefore be well advised to sit down with their IT department and determine how often each day their employees visit free translation sites and to come up with an alternative.

Pawel Walentynowicz

Het Financieele Dagblad (“The Financial Journal”) is a daily Dutch newspaper, founded over 200 years ago. It is focused on business and financial matters.